“So far as Bloody Sunday in Derry, January 30th, 1972 is concerned, those words like Sharpeville, Tiannemen Square, Amritsar, Kent University, carry associations that go far beyond people, place or time. They have passed from their ordinary meaning into a universal currency of language which defines a situation in which the Security Forces of a state use unjustifiable and unacceptable repressive violence against its own citizens.

When those words pass in to that currency of vocabulary, which is of itself a definition, they also carry images which register specifically within the communities and invoke in other places in the world images which are parochial to them, but nonetheless compelling.

The images Bloody Sunday evokes for the people of this community and in this city are many and varied. One, and perhaps the most striking, is the image of Father Daly saying the last rites over young Jack Duddy on the cold concrete of a car park in Rossville flats. The image of Father Daly making his way across that open ground, down Chamberlain Street, turning up Harvey Street, being presented with the force of arms in terms of soldiers and armoured vehicles, waving a white hanky, bloodstained.

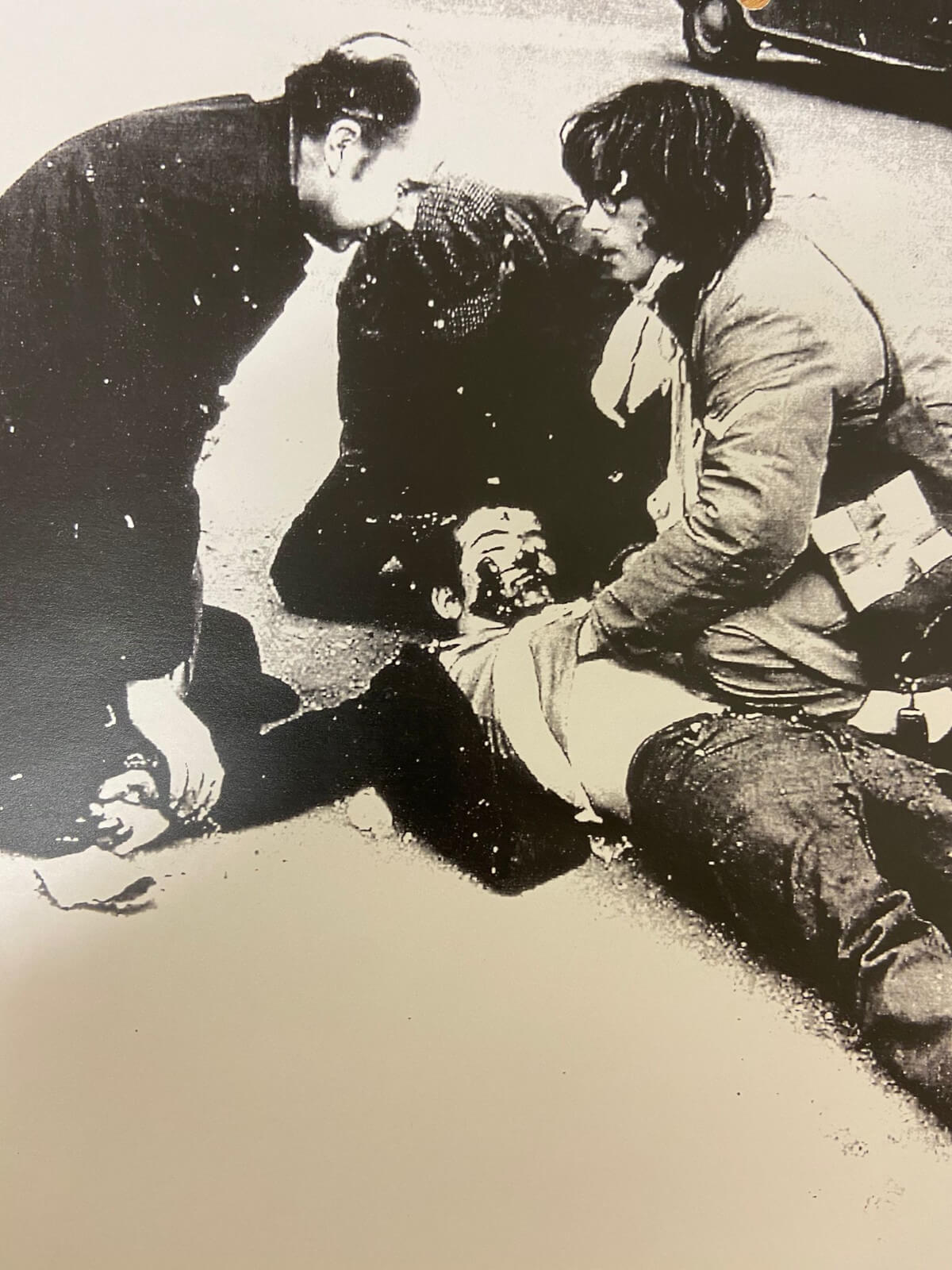

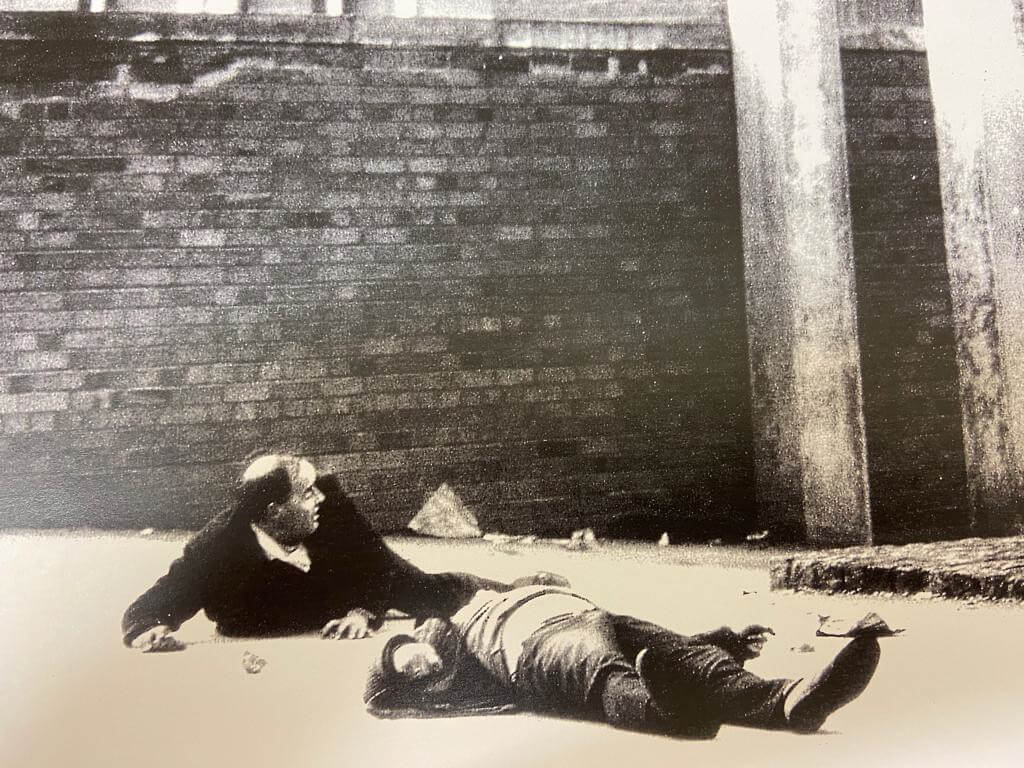

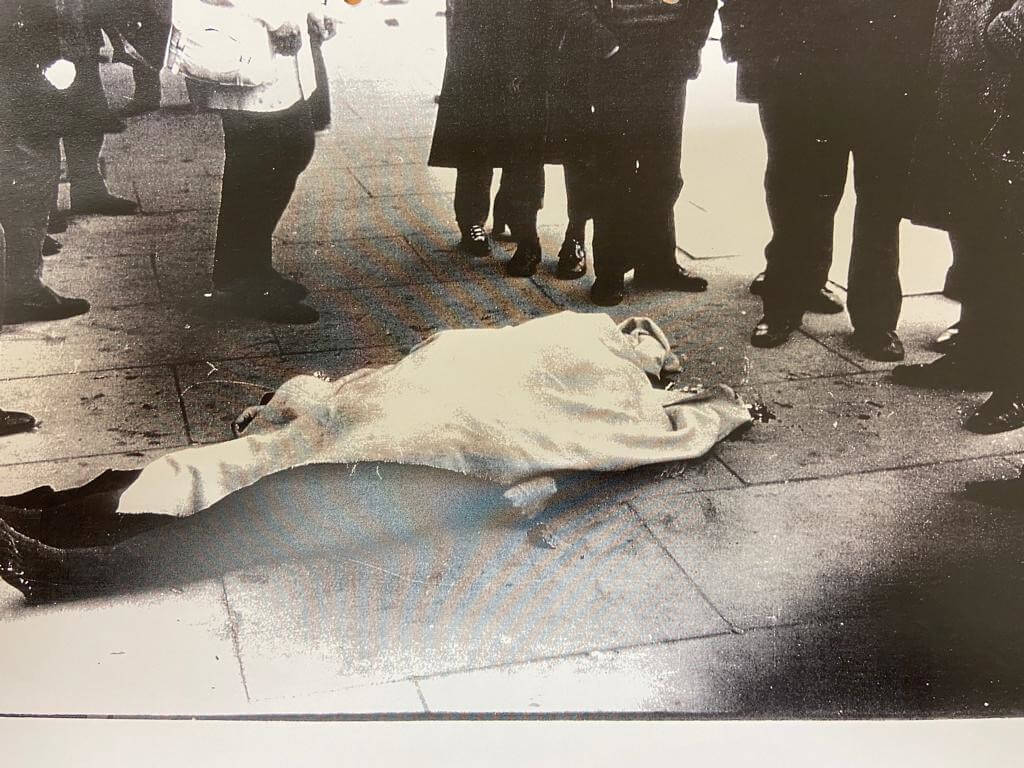

It is the image of Patrick Doherty lying behind Rossville flats, with his eyes being closed by Leo Day from the Knights of Malta. It is the image, both visual and vocal, of Geraldine Richmond, cowering behind block 1 of the Rossville flats, between the entrance and the telephone box, having witnessed the prone body of Hugh Gilmore, who struggled round the corner to die, and then witnessed Barney McGuigan, compelled by the inner voice of his own humanity to go out to the attendance of Patrick Doherty, who did not want to die alone. And the photograph which reflects the inhumanity which his humanity brought about, of his life blood ebbing away, again on the cold concrete.

The image of someone having to strike a poor girl, Geraldine Richmond, in order not only to relieve the dreadful tension that she felt at that moment, but the dreadful feelings of inadequacy that it summed up in all of those around her.

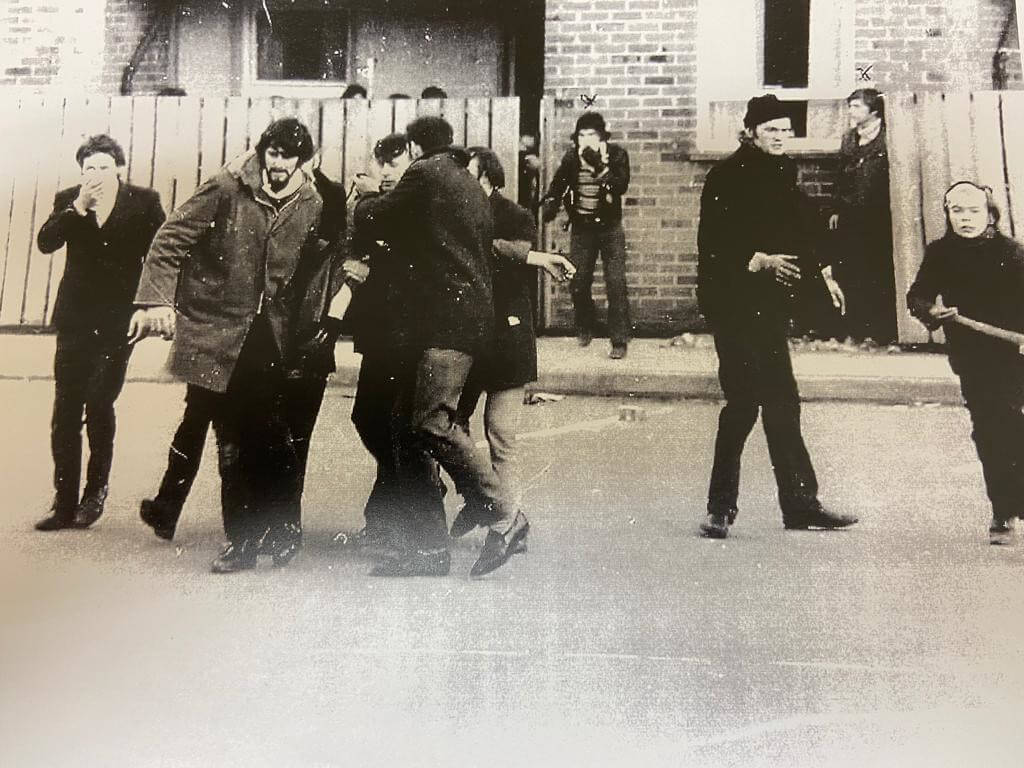

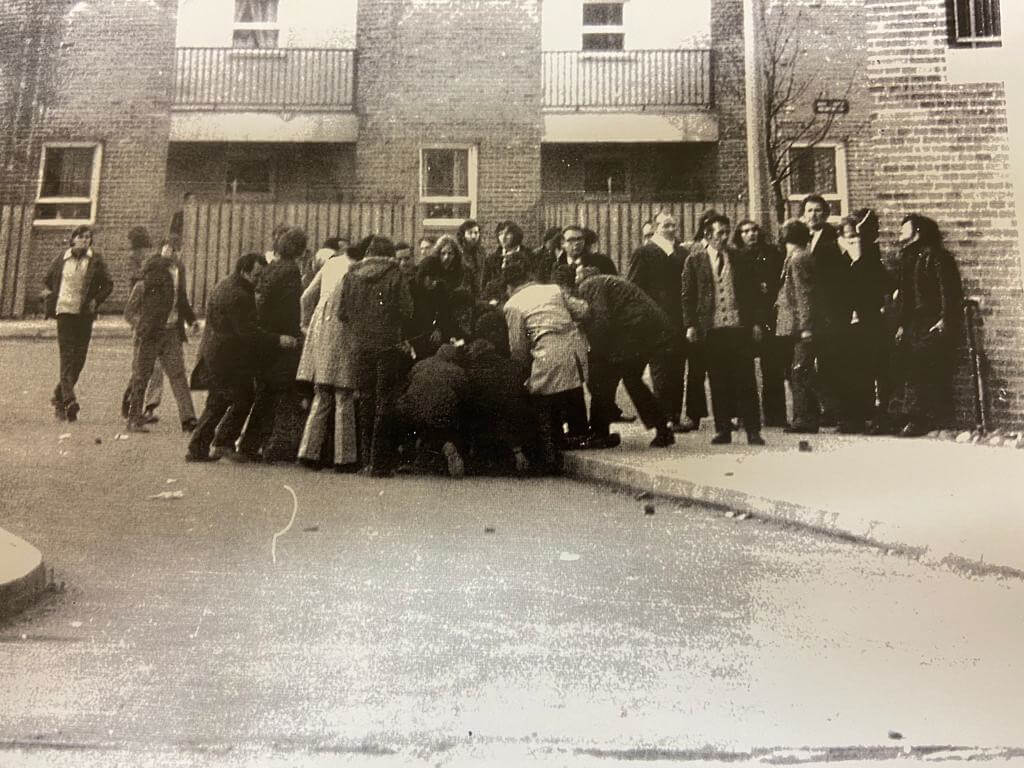

It is the images of the other individuals whom one sees quite literally moments from death. The image of Michael Kelly standing, facing down Rossville Street towards Wilford’s wall and moments later lying prostrate on the ground, being attended by his friends. The image of the others all gathered there; the image in fact of Michael McDaid walking back through the barricade, the casual look of bewilderment, failure to understand what was happening and moments later, dead.

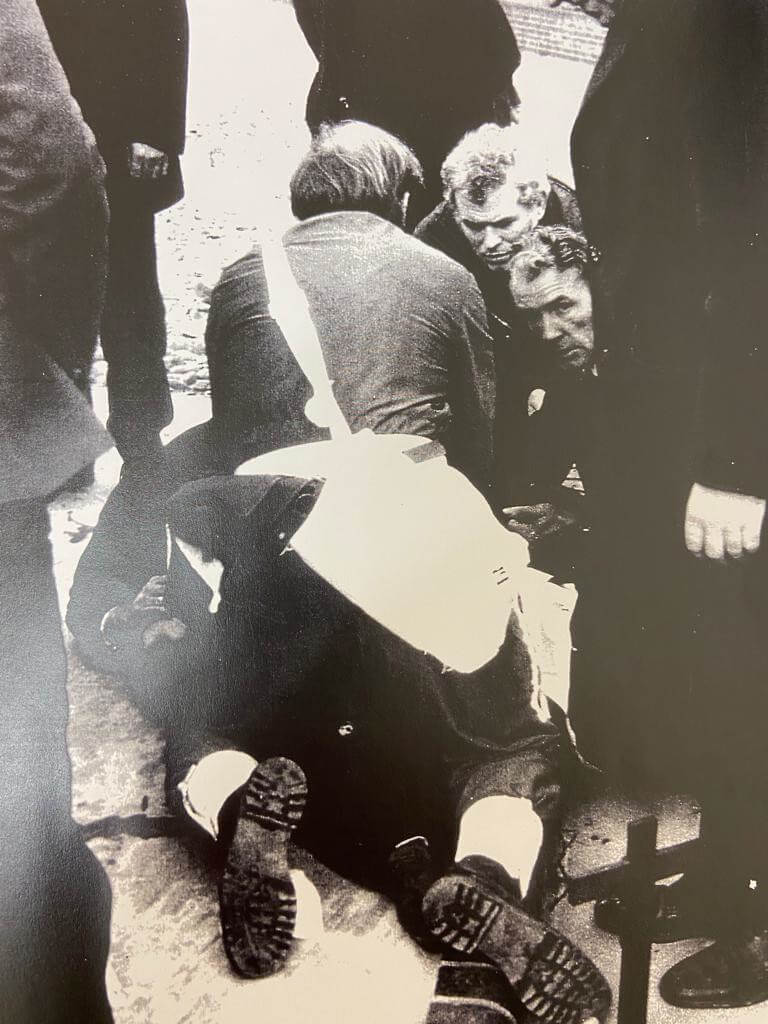

The image of Michael Kelly’s body having been brought back into Glenfada Park for the protection of the gable, such as it could provide. The image of the

others all gathered round. The image of John Barry Liddy, the barman in the officers’ mess, in a desperate attempt to understand what is going on, waving to others.

The image of Michael Kelly having been brought round into Glenfada Park, being surrounded by Michael Quinn, Jim Wray, Pearse McCaul, Charlie McLaughlin, knowing that within minutes Jim Wray would be killed, Michael Quinn would be shot through the face.

The image also of William McKinney and his distinctive glasses, standing at the entrance to Glenfada. Within minutes he also would die. It is the images also of Gerard Donaghy and Gerard McKinney lying in Abbey Park, again being attended just seconds after or moments after the entry of the first Regiment of the Paratroop Regiment into Glenfada Park.

The images are many, they do create a sense of emotion within a community such as this…”