Bloody Sunday PSNI Murder Investigation Report – Ciarán Shiels of Madden & Finucane speaks to investigative journalist Lara Whyte.

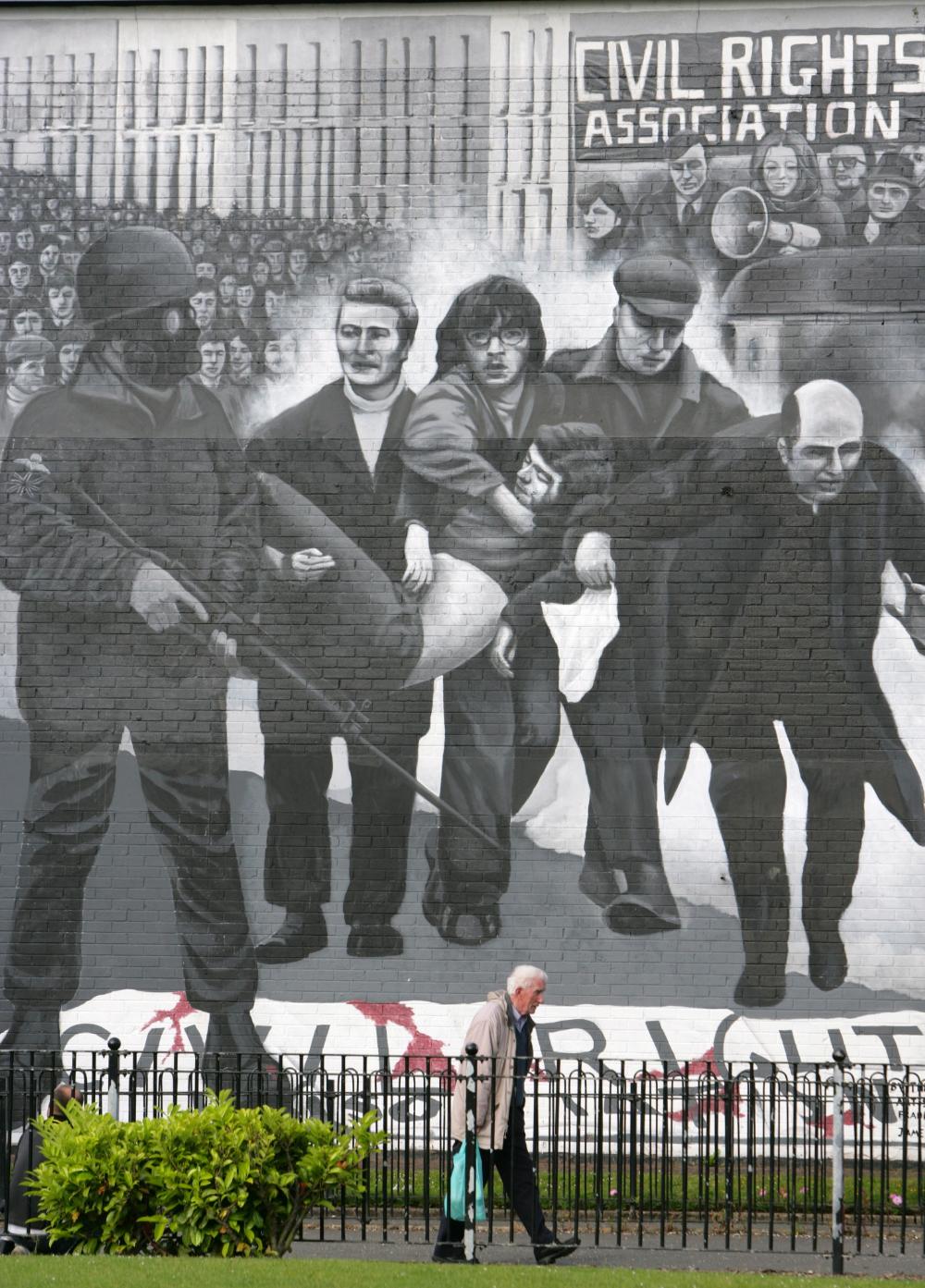

A man walks past a Bloody Sunday mural in the Bogside, Derry

Relatives of those killed in Northern Ireland’s infamous Bloody Sunday massacre have denounced the police investigation into the murders after being told that 55 soldiers present that day are refusing to be questioned.

Kate Nash, whose 19-year-old brother William was among 13 people shot dead when British Army paratroopers fired at civil rights protesters on January 30, 1972, claimed the UK government and Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) were engaged in another cover-up. Soldiers were told to fire upon unarmed demonstrators, she believes, rather than the shooting being the result of troops disobeying orders as a previous major inquiry claimed.

The massacre took place during a demonstration in the city of Derry in the early years of the so-called “Troubles,” a 30-year violent conflict centered on the status of Northern Ireland. Between 10,000 and 20,000 people had gathered to protest against a policy known as internment, where people suspected of being a member of a terrorist group such as the Irish Republican Army — Catholic insurgents who wanted Northern Ireland to break away from British rule — were being rounded up and detained without trial.

The overwhelming majority of those arrested were Catholic — 1,874 out of the 1,981 detained in total between 1971 and 1975 — and the march, organized by a group called the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association attracted mainly (but not exclusively) Catholic men, women and children.

After the march was prevented from entering the city center by the British Army, it moved to “Free Derry Corner” in the Bogside, a Catholic area of the city that still prides itself in being separate from British state. Soldiers from the British Army’s elite Parachute Regime moved into the Bogside after bricks where apparently thrown at one of the barricades erected by the army.

Within 30 minutes they had shot 13 men dead and injured more than a dozen. A fourteenth victim later died of his injuries.

After the massacre, the army claimed they had been attacked first and accused the protesters of being terrorists and members of the IRA — but this has always been rejected as false by those there and was later officially discredited.

A 12-year public inquiry into the killings led by the British judge Lord Mark Saville ultimately concluded in 2010 that none of those killed were posing a threat, that the paratroopers fired the first shots, that they had fired on fleeing unarmed civilians, and shot dead a man who was already wounded.

No action was taken in response to the Saville inquiry by the PSNI or judicial authorities for two years, a source of much anger for relatives. In July 2012 a murder investigation was finally launched following public pressure.

Ciaran Shiels from Madden and Finucane solicitors, a lawyer representing the families, told VICE News that the current investigation has been an uphill battle from the beginning.

“It is important to bear in mind that after the Saville inquiry reported in 2010, it wasn’t a matter that the PSNI of its own volition took to investigate — even though Saville had said that these people had been shot without justification,” he said. “We had to write both to the Chief Constable and the Public Prosecution Service saying there is prima facie evidence here of attempted murder on a grand scale and what are the PSNI going to do about it?”

Progress has been painfully slow — no arrests have been made, and families were told that the military suspects — i.e. the members of the army identified in the Saville report as having fired the fatal shots — have yet to be interviewed. In the latest update given to the families, the PSNI’s senior investigative officer Detective Chief Inspector (DCI) Ian Harrison said 34 military witnesses and 310 civilian witness statements had been recorded.

In a statement to VICE News, a PSNI spokeswoman confirmed that 55 military witnesses and 239 civilian witnesses have “declined to engage with the team.” She stressed that the 55 soldiers were not suspects.

“Those military witnesses who have refused to engage are regarded as being potential witnesses to events,” said the statement. “Please note, they have refused to engage in terms of recording witness statements, not interviews. It should be noted that these soldiers are witnesses, not suspects, and are therefore not obliged to speak with us.

“The seven military witnesses to be interviewed over the coming months fired shots. That is the focus of the investigation at this stage and these interviews will take place over the coming months.”

For Kate Nash and the other families of the dead, it has felt like another bitter blow in their long campaign for justice. She criticized the PSNI, saying the glacial pace of the police investigations was “soul-destroyingly frustrating.”

“The police told us that they couldn’t compel them to come forward, but that is absolute nonsense — because these 55 witnesses to massacre should be fully aware there is another crime called withholding evidence, and we know that very well. They could do the right thing now, but they don’t. In some of the cases, they have the bullet, they have the gun that leads to the solder and the police agreed this is solid evidence, so why haven’t they arrested him?”

Shiels, the solicitor, said it didn’t appear to have occurred to the police that they could and should compel the army members to co-operate, and that they could be charged and jailed for failing to do so.

“In respect of murder, when one withholds information, it can be punishable by up to ten years imprisonment,” he said. “It is an arrestable offence, and the position of the families would be that soldiers who are suspected of withholding relevant information should be warned that they are themselves at risk of arrest and prosecution. So it came as an issue of very serious and immediate concern to the families that there seemed to be an attitude of the PSNI that is someone doesn’t want to co-operate with us there is nothing we can do about it. ”

He also said stressed that a great number of civilian witnesses that day would have been fleeing for their lives or hiding from the barrage of bullets the soldiers were firing, while those soldiers not firing at the crowd would have had a privileged and safe view.

The PSNI would not be drawn on whether the interviews the army members gave could be used as evidence, or what effect the lack of co-operation would have on their investigation — only confirming they were beginning to interview those soldiers identified as firing the shots under caution.

Nash believes that the findings of the Saville inquiry, as scathing as they were, did not reveal the full truth of the events of the day, and there are political reasons why the police are not investigating the murders fully. The government, she says, is afraid of what the soldiers might say if they were in court.

“It is a terrible blow to us all. They could arrest soldiers right now and the fact is they are not. The government doesn’t want to take soldiers to court, and I’ll tell you why — because it went further than those soldiers,” she said. “[Saville] concluded that one officer and nine soldiers were responsible for what happened — [the report] said the officer had disobeyed orders but the same officer was actually given an OBE at the end of 1972 and those soldiers were all given medals of honor. If they were given medals then obviously they had done good work. They were ordered in there, we know that.”

The events and the smears against the unarmed victims that came after were catastrophic for the people of Northern Ireland, but for the families of those who died, the tragedy remains personal above all else.

“When William was shot, my father ran out under a hail of bullets try and help him, and he was shot and injured in his arm and in his side,” Nash told VICE News. “William’s body was dragged out of his arms by the army and he was taken into the back of a [military] van. My father never really got over the way they dragged his body away from him like that.”

Her mother had been in hospital and did not attend the march, and was only well enough to be told about the death on the day of William’s funeral.

“She was well sedated when my father and the local priest told her, and she didn’t react — there was just silence. It was when she got home a few days later she walked through the front door, she just started screaming his name, and that screaming lasted for a long time. A very long time.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.