Extensive feature in today’s Guardian on Madden & Finucane’s successful appeal of Martin McCauley’s 1980’s firearms conviction and on our continuing involvement in the Stalker Sampson inquests on behalf of several bereaved families.

Martin McCauley was shot three times by police in the 1982 attack that killed his friend Michael Tighe.

When Martin McCauley was 19, he was shot by police as an IRA suspect. His best friend was killed. The RUC has always denied that it had a shoot to kill policy, but now fresh evidence is emerging.

Martin McCauley and Michael Tighe were country boys. They grew up a stone’s throw from each other, on smallholdings that sat on opposite sides of a narrow, hedge-lined lane. Derrymacash, the Northern Irish village where they went to school and played Gaelic football, was a mile away. Beyond that lay the expansive waters of Lough Neagh. The boys helped out on each other’s family farms: in the summer they cut and baled hay together; in the winter they rode tractors. In the summer of 1982 they had bought a motorbike, a scrambler, to tear across the bogs of north Antrim and perform wheelies along the local boreens.

On 24 November that year, a Wednesday, Tighe spent most of the day on his parents’ smallholding, looking after the pigs. At the end of the afternoon, as the light was about to fade, McCauley kickstarted their bike and they rode it to an empty redbrick bungalow about half a mile away. They parked up and went into a ramshackle hayshed at the back of the house.

The first two bullets came through the window. The boys had heard no sound, no hint whatsoever that anyone had crept up to the front of the hayshed; just two very loud bangs. Tighe, who was sitting on a stack of hay bales, toppled backwards. McCauley, standing next to the window, froze. “Next thing, the whole of the wooden doors to the barn exploded inwards,” he recalled. “They just machine-gunned it. I was standing up and trying to press myself against a hay bale, but I couldn’t get any cover. So I crouched down and tried to move backwards across the doorway. I was trying to get out of the way like this,” he said, shuffling backwards to demonstrate. “It was like everything had slowed down. I don’t know where I was hit first. One of the shots hit me in the back of my left shoulder and exited through my throat. Look: you can still see where it came out. Another hit me around the top of my spine and exited through my right armpit. The third hit me in my right thigh near the groin and came out of the outside of my thigh.

“Someone came into the hayshed and hit me on the back of my head, and I was dragged through what was left of the doors. The pain was just excruciating. The best way that I can describe being shot is that it’s like someone walked up to you and hit you with a red-hot sledgehammer. I was just lying there. And with every heartbeat the blood was pumping up in the air from my thigh.” A man pointed a rifle at his head and threatened to finish him off. He thought he was going to die. Tighe was out of sight, behind the hay bales. “I didn’t know it then, but Mickey was dead. He’d been shot twice in the heart.”

McCauley was 19, an alleged IRA volunteer and bomb-maker: a suspected killer. Tighe, one of six children, was “a fresh-faced lad of simple needs”, with no involvement in the conflict, according to the subsequent assessment of a senior policeman. He was 17. His killing brought Northern Ireland’s death toll to 2,487. But Michael Tighe’s death was different, because the shots that killed him, and the subsequent cover‑up, were part of a dark episode in the undeclared war in the north, in which it was possible to glimpse the British state fighting terror with terror.

The old barn in Derrymacash, County Armagh, where the shooting took place.

The battle to establish the truth about what happened in the hayshed has dragged on for three decades – a subplot in the wider tragedy of the Troubles. But some of the details of that afternoon are only now starting to emerge. Two highly classified reports by senior policemen, John Stalker and Colin Sampson – which have never been released to the public – concluded that senior Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) detectives and MI5 officers were involved in a conspiracy to suppress the truth about Tighe’s killing. Sampson’s report, portions of which the Guardian has seen, is particularly critical of MI5, describing the agency’s conduct as “reprehensible” and “patently dishonest”.

Next year, after 34 years, inquests will finally be held into the deaths of Tighe and five other men, all of whom were killed within a few weeks not far from the hayshed. Northern Ireland may have been largely at peace for almost two decades, but it is a peace that remains haunted; even the dead, it seems, cannot lie down to sleep.

* * *

One afternoon in late October 1982, four weeks before the shootings at the hayshed, the police received a call, claiming that someone had been prowling around the farms that line the southern shore of the lough and had stolen a battery from a tractor; three officers were despatched to make inquiries. Travelling in an armoured Ford Cortina, they made their way along a route leading to the M1 motorway, a straight stretch of road known locally as Kinnego embankment. The IRA had built an enormous bomb inside a culvert under the road, and when it was detonated by a control wire, the Cortina was hurled 70ft in the air. All three officers were killed instantly. One was 26 and had been married for a month; the other two had five children between them.

Jack Hermon, the chief constable of the RUC, was driving nearby with his wife. “We stopped momentarily at a roundabout,” he wrote in his memoirs. “As we did so, we heard the explosion, and our driver pointed to the smoke and debris erupting on the skyline.” The blast left a crater 15ft deep and 40ft wide. The killing of the three policemen was not merely distressing for their fellow officers – it was maddening. The home-made explosives used in the bomb were supposed to have been under surveillance.

Michael Tighe was shot dead at the age of 17.

Several weeks earlier, an informer within the ranks of the local IRA had contacted his handlers from special branch, the intelligence-gathering unit of the RUC, and told them that around 1,000lb of explosives had been smuggled across the border from the Irish Republic. It was being stored in a hayshed near Derrymacash, 10 minutes’ drive from Kinnego. The informer identified three local men as members of an IRA unit that was planning to carry out a bomb attack. Two of them, Eugene Toman and Sean Burns, were 21 and from the nearby town of Lurgan. The third, the informer said, was Martin McCauley.

The farmland in that corner of north Armagh is relentlessly flat, and there was not much woodland cover nearby, so a decision was taken that the hayshed should not be watched. Instead, an MI5 technician, accompanied by a British special forces soldier, broke in and wired a microphone into the rafters, and installed a movement sensor beneath the black plastic bags containing the explosives. The devices were monitored by both British soldiers and RUC officers, at an army post a few miles away, and the transmissions were tape recorded.

Somehow, the IRA had managed to remove the explosives from the hayshed without the army monitors hearing anything, and had used them to construct the bomb that killed the three police officers at Kinnego.

Fifteen days later, Toman and Burns were dead, along with a third local IRA member, Toman’s cousin Gervaise McKerr, a 31-year-old joiner and father of two small boys. All three were shot by an RUC squad called the Headquarters Mobile Support Unit (HMSU), which had been trained by the SAS regiment in what subsequent court evidence would describe as “firepower, speed and aggression”, and operated under the control of special branch. The RUC issued a press statement, saying that the three men had been travelling in a car that tried to run over a policeman at a roadblock on the outskirts of Lurgan. “As he attempted to throw himself out of its path, he was struck by the car and injured,” the statement said. “Other police opened fire on the vehicle which drove on in an attempt to escape.” All three men were killed. The policemen who was struck by the car was not seriously hurt.

The shooting happened so close to McKerr’s home that his family could hear it while watching Top of the Pops on television. Eddy Grant was singing I Don’t Wanna Dance, while outside the sound of the shooting went on and on. None of the three men who died had been armed. McKerr and his wife Eleanor had been considering emigrating to Canada. “How different life would have been,” she later wrote. McCauley heard the news at his parents’ home. It was not long before local musicians were singing a rebel song: “The three lie in a soldiers’ grave in a churchyard near the town …”

Thirteen days after that, Tighe and McCauley were shot in the hayshed by members of the same small police unit. The RUC press release said that a patrol had noticed an armed man enter the shed and decided to investigate. “They were confronted by two men armed with rifles. Police opened fire and the two gunmen were hit. One man died at the scene and the other, who was seriously injured, was taken to Craigavon hospital.” The statement added that three rifles were found at the scene and the search was continuing. No mention was made of any listening devices or movement sensors, nor of the soldiers who were monitoring the shed from the listening post.

At Craigavon hospital, McCauley underwent emergency surgery. After being wheeled out of theatre he was arrested and charged with possession of three rifles that were recovered from the hayshed. He was also told that his friend was dead. McCauley watched news coverage of the funeral on television in an intensive care ward. “It was a massive funeral. It seemed unreal, watching the family and our friends and neighbours walk behind Mickey’s coffin.” Then he was transferred to a secure unit at a hospital in Belfast, where doctors decided he needed nerve grafts to repair damage to his right arm.

Eighteen days after the shooting at the hayshed, two more men were shot dead by officers of the HMSU, this time in Armagh, south-west of Belfast. Like the men shot dead in Lurgan, Seamus Grew, 30, and Roddy Carroll, 21, were terrorists: members of the Irish National Liberation Army. They were also unarmed. The subsequent RUC press statement was unusually detailed. It said that the two men had been in a car that had driven through a police checkpoint, and that the vehicle had been chased “at speed’’ before being forced to a halt. “The driver jumped out of the vehicle and the police, believing they were about to be fired on, themselves opened fire. Both occupants were shot.”

There were a number of problems with the police statements about these three incidents – the principal one being that they were untrue.

* * *

In both London and Dublin, ministers and officials had hoped that 1982 would offer some respite after the turmoil that followed the hunger strikes of the previous year; a year in which some political progress might be made in the north. Unemployment was rising sharply, however, and by the end of the year more than one in four men were out of work. And the bombings and shootings continued.

By the time of the deaths of Carroll and Grew, many nationalists in Northern Ireland were enraged by the killings, and senior members of the Roman Catholic clergy were demanding an independent inquiry. Sinn Fein accused the police of carrying out summary executions. The suspicion grew that the RUC was running some sort of a death squad. Few people were prepared to use such a term, however: instead, someone coined the ambiguous phrase “shoot-to-kill”. Northern Ireland secretary Jim Prior immediately denied there was any “shoot-to-kill policy”. There was, he said, “a policy of capturing and dealing with terrorists”, but he added that if people who were suspected of being armed broke through a roadblock, “they must accept the security forces have to take the necessary action”.

In June the following year, as a result of pressure from the director of public prosecutions for Northern Ireland, the RUC conducted fresh investigations into the two shootings. Eventually three members of the HMSU were charged with the murder of Eugene Toman, who had been shot by a constable named David Brannigan.

Bullet holes in the window of the hayshed in Derrymacash where Martin McCauley and Michael Tighe were shot.

When they went on trial in May 1984, the three men insisted that they had believed their lives to be in danger when they opened fire. The judge, Lord Justice Gibson, sitting with no jury, accepted their defence. Announcing his verdict, Gibson said he believed the officers to be “absolutely blameless”, adding: “That finding should be put on their record along with my own commendation as to their courage and determination for bringing the three deceased men to justice, in this case, to the final court of justice.”

A fourth police officer, Constable John Robinson, was charged with the murder of Grew. Like a number of other members of the HMSU, Robinson was English and a former soldier. The prosecution case was that he had emptied his pistol into Carroll from a few feet, reloaded, walked around the car to where Grew was climbing out, and shot him from a distance of a few inches. It emerged during the trial that Grew and Carroll were thought to have been in contact with the INLA leader Dominic McGlinchey – who was believed to have ordered the bombing of a disco in a pub near Derry a few days earlier, in which 11 soldiers and six civilians had died. The police had information that McGlinchey, the man the popular press dubbed “Mad Dog”, would be in that car with Grew and Carroll.

Although Robinson was cleared on the same grounds as his colleagues – that he believed his life to be in danger – his trial did not run smoothly. He admitted in court that he had not told the truth when interviewed by detectives investigating the shooting. He told the judge that senior officers had ordered him to give a false account in order to conceal that the dead men had been under surveillance by an army unit, and also to hide the fact that intelligence about them had been supplied by a special branch informer. Furthermore, Robinson said, there had been no roadblock, and no high-speed chase.

* * *

As a consequence of Robinson’s admissions, the RUC was compelled to request an investigation by an outside force. John Stalker, the deputy chief constable of Greater Manchester police, agreed at the end of May 1984 to examine all six deaths. Nobody at special branch said a word to Stalker about the Kinnego embankment bombing, informers, or electronic surveillance. But he and his team soon began to work it out. He established that Toman, Burns and McKerr, like Grew and Carroll, had been followed before they died. He realised that no attempt had been made to halt the green Ford Escort in which the first three men were travelling, and no policeman had been struck by it. The officers of the HMSU had chased the car for 500 yards while firing 108 shots at its occupants. They had then been ordered to leave the scene while special branch detectives removed many of the cartridge cases. When investigators from the police Criminal Investigation Department arrived, they examined the wrong location.

Stalker also found that the members of the headquarters mobile support unit had been told to give false accounts to investigating detectives – based on press releases that had been prepared before the shootings, in order to provide a response to the inevitable questions from journalists. These accounts were then slightly tweaked to fit in with the events as they had unfolded. The same measures had been taken before Grew and Carroll were shot dead.

When McCauley went on trial in early February 1985, charged with possessing the three rifles found at the hayshed, Stalker sat in on the proceedings. Between hearings he chatted with McCauley’s solicitor, Pat Finucane, much to the anger of watching RUC officers, who told Stalker that they regarded Finucane, who had represented many people accused of being republican terrorists, as being “worse than an IRA man”. McCauley told the court he had been looking after the property for the elderly woman who owned it, and had climbed through an open window when he saw the rifles inside. They were heavily rusted Mausers of pre-second world war vintage. There was no ammunition. When the police who shot the two teenagers gave evidence, they admitted their superiors had presented them with a false story to explain why they had gone to the building (they had not seen an armed man in the vicinity), but insisted they had opened fire after shouting two warnings – “Police, throw out your weapons!” – and only when the pair pointed the rifles in their direction. The trial judge decided the police officers’ evidence was so unreliable that he would need to discount it completely. But he concluded that McCauley was also lying, and gave him a two-year prison sentence, suspended for three years.

In his report on the affair, which has remained secret for 30 years, Stalker described how the regional head of the CID, the police department that investigates serious crime, had arrived at the hayshed after the shooting only to be told by a more junior special branch officer that “the scene of the incident was out of bounds” to CID. “Resignedly, he had a meal at Lurgan police station before arriving at the scene about one and a half hours after the incident had occurred,” Stalker reported. The senior detective could see special branch were busy at the hayshed, but chose not to question their presence as he knew he would not be enlightened. “If this were an isolated instance I might accept it as partly understandable,” Stalker wrote in his report, “but the same thread of special branch paramountcy runs through all the incidents. Such a situation does not develop overnight and must, it seems to me, have high-level endorsement.”

Stalker discovered that the informant who had told special branch about the explosives at the hayshed had also provided information about Toman, Burns, McKerr and McCauley. He suspected that this man was not only an informer, but an agent provocateur, who had planted the old rifles at the hayshed. The surveillance was being maintained, and anyone who went to take the weapons was liable to be attacked. Stalker also found out how much money was being paid to this spy inside the IRA: it amounted to many thousands of pounds. But he never discovered the informer’s identity, and nor did anyone else outside a tight group of special branch detectives and MI5 officers. In Derrymacash, suspicion fixed upon an individual close to young Michael Tighe’s family, a man who vanished around the time Stalker began making his inquiries, and who has never been seen since.

Stalker began to think that special branch, supported by MI5, might be using informants to lure terrorism suspects into pre-planned ambushes, mounted by police officers who were indeed shooting to kill.

* * *

Stalker had been on the case about six months before he learned that the events at the hayshed in October 1982 had been recorded. There was a sequence of tapes from the listening device, and the key tape – which captured the moment when the police opened fire – was known as Tape 042. There could be no better piece of evidence in the quest to establish whether or not some sort of shoot-to-kill policy had been operating: if a warning had been shouted it would have been audible on the tape; if not, it would be possible that the two young men had been ambushed.

In the book about the affair that he later published, Stalker wrote: “I passionately believe that if a police force of the United Kingdom could, in cold blood, kill a 17-year-old youth with no terrorist or criminal convictions, and then plot to hide the evidence from a senior policeman deputed to investigate it, then the shame belonged to us all. This is the act of a police force out of control.” Stalker was wrong, in this respect. The RUC and its HMSU were not out of control: far from it.

Stalker was aware, when he arrived in Northern Ireland, that he was investigating members of a police force that faced unique challenges. By the time of the Kinnego embankment bombing, 168 RUC officers had lost their lives. He also appreciated that the intelligence-gathering activities of special branch played an indispensable role in the RUC’s operations. What he had not been told was that a strategy – devised by MI5 and adopted by the RUC in complete secrecy – had prioritised the acquisition of intelligence over the solving of crime and the prosecution of offenders, in a way that utterly transformed policing tactics in Northern Ireland.

Stalker had not been informed that, within days of being appointed chief constable of the RUC in January 1980, Jack Hermon had asked MI5 to examine the role of intelligence-gathering in police operations. The study was conducted by Patrick Walker, a senior MI5 officer in Northern Ireland, who would go on to become director general of the agency in 1987. Today, the Walker report remains a state secret, but the confidential police instruction that was issued to senior CID officers, ordering them to implement its key recommendations, has surfaced. Dated 23 February 1981, this document makes clear that Hermon had accepted that the recruitment of agents from within the ranks of the paramilitary organisations should take priority over the solving of individual crimes; that CID should arrest no one without first consulting special branch, in order to avoid the inadvertent detention of such agents; and that the requirements of special branch and MI5 should take precedence over the work of the CID.

Knowing nothing of the existence of the Walker report, and the way in which it was guiding counter-terrorism tactics, Stalker decided that he should pursue the recording from the hayshed. And having made his decision, Tape 042 became an obsession.

* * *

Martin McCauley, meanwhile, was still making sense of the extensive covert surveillance operation that had been disclosed at his trial. “It never occurred to us at that time that they could bug buildings,” he said earlier this year. “We were country people: we didn’t even have a telephone.” People in north Armagh began to speculate that there could be dozens of such listening devices in place, in the Lurgan area alone. They may well have been correct. But McCauley was not surprised that Tape 042 was not played in court. “If they had been telling the truth about the shooting they could have just played the tape straight away in court. But they couldn’t do that because they would have been up for murder.” Returning to Derrymacash, he was repeatedly stopped and questioned by police, and followed, he said, by men he recognised to be off-duty members of the Ulster Defence Regiment, the locally recruited British army unit. He found work as an engineer, married his girlfriend, Cristín, and the first of their three children was born. But facing what he describes as harassment, the couple moved south of the border, to what they call the Free State. They settled first in Kildare – “we chose it with a pin in a map” – and then Monaghan.

Life was not so very different down south. The special branch of the Garda Síochána were frequent visitors to the McCauleys’ home. “The guards were even worse than the RUC,” McCauley said. On one occasion an officer pointed a handgun at his head. On another, the couple were shocked – as Irish republicans residing in the Irish Republic – by a guard detective’s brusque suggestion: “Why don’t you fuck off back to Thatcherland?” Cristín laughs and shakes her head. “That was so insulting on so many levels.”

The war in the north dragged on. Lord Justice Gibson, the judge who had commended the men of the HMSU for having brought Toman, Burns and McKerr to “the final court of justice”, was murdered in April 1987. The IRA concealed a 500lb bomb inside a car and detonated it as Gibson drove past, then issued a statement in which they condemned the judge for supporting “RUC executioners” and said that he too had been brought to the “final court of justice”. His wife Cecily died alongside him. Two years later, McCauley’s solicitor, Pat Finucane, was shot dead in front of his wife and children. Four years after that, David Brannigan, the police officer who had shot dead Eugene Toman – and who believed he had been hung out to dry by his superiors – shot himself.

Over the years, McCauley continued to be arrested and questioned on both sides of the border. He believes that this happened four or five times, but he can no longer recall for certain. Cristín was arrested once. The authorities in both countries had come to the conclusion that her husband was an expert in the construction of home-made mortars as well as bombs. In February 1991, at the height of the Gulf war, the IRA attempted to assassinate prime minister John Major and his war cabinet as it met in Downing Street, firing three home-made mortars from a van parked a few hundred yards away in Whitehall. One shell exploded in the rear garden of Number 10, injuring four people. McCauley, who was in Ireland at the time, was immediately picked up for questioning. The following month the family moved back north, to Lurgan, where McCauley engaged another well-known lawyer, Rosemary Nelson. They stayed in the town for seven years, until April 1998, when someone left a pipe bomb outside their front door. They packed their bags again and moved back to Kildare. The following week the Good Friday agreement brought the conflict largely, but not completely, to an end: the following year, Rosemary Nelson was killed by a car bomb.

* * *

Stalker, meanwhile, having made his decision, pursued Tape 042 with the utmost vigour. He wanted not only the transcript of the recording, but the tape itself, and the logbooks that recorded where it had been stored and who had listened to it. The RUC refused to hand over this material, and after much stalling, Hermon told Stalker it belonged to MI5. Stalker later recounted that MI5 had agreed that he should be given the tape, but Chief Constable Hermon still refused. Hermon began avoiding Stalker and failed to return his calls.

After eight months of this, at a meeting at MI5 headquarters in June 1985, Stalker had been told by the head of the agency’s operations in Northern Ireland that MI5 would never stand in the way of a murder investigation and that it would hand over all the information in its possession. No material was produced, then or later.

Stalker submitted an interim report in September 1985, in which he said there was enough evidence to indicate that the five men shot dead in their cars were unlawfully killed by police officers. He also made clear that he was going to continue his search for evidence of a shoot-to-kill policy.

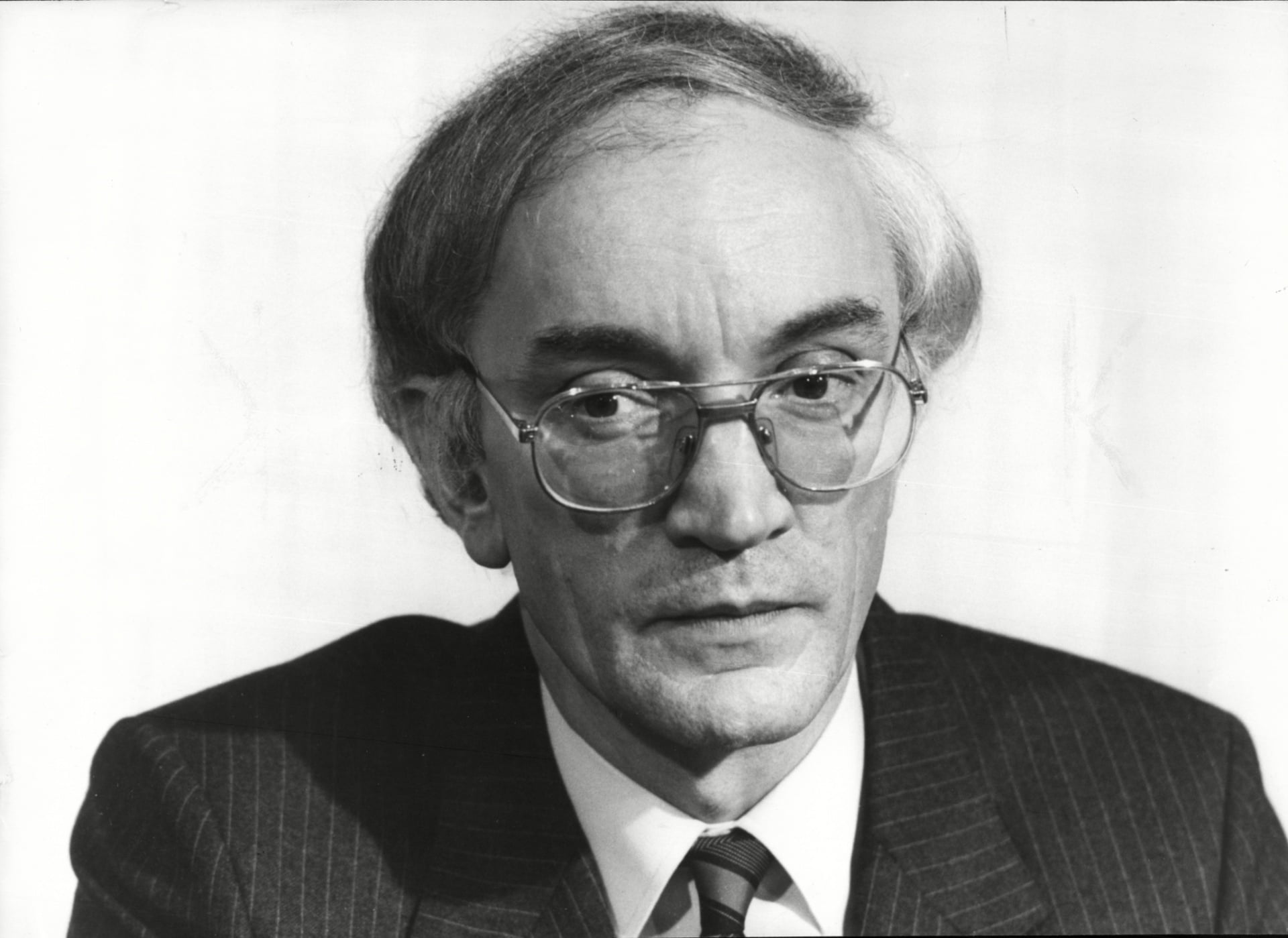

Following a police investigation, John Stalker was suspended from duty and accused of consorting with criminals.

Later that month, police in the north-west of England opened a criminal inquiry into one of his friends, Kevin Taylor, a successful Manchester businessman. Shortly after that, Stalker too came under investigation. In a widely publicised scandal, Stalker was suspended from duty and accused of consorting with criminals. The allegation was that Taylor had links with gangsters, known locally as the Quality Street gang, and that Stalker had attended social events with a number of them. Stalker was adamant that this was a pretext to remove him from the shoot-to-kill inquiry. It was not until August 1986 that Stalker was fully exonerated and returned to work. When it emerged that his efforts to defend himself had resulted in a £22,000 legal bill – and that the police were expecting him to pay it himself – donations from the public began to arrive at his office. Stalker left the police service for good in 1987. He had devoted two years of his life to his inquiry, and concluded that he had failed.

Stalker’s friend Taylor was subjected to a four-year police investigation which resulted in him being charged with fraud, but when the case came to trial, the prosecution withdrew. When he sued Manchester police, alleging it had been guilty of malicious prosecution, the force settled out of court for a sum in excess of £1m.

In the meantime, Colin Sampson, the chief constable of West Yorkshire, had agreed to take over the shoot-to-kill inquiry. He produced three reports, all of which were classified and not one of which led to any prosecutions. In January 1988 the attorney general, Sir Patrick Mayhew, told the House of Commons that the director of public prosecutions for Northern Ireland had concluded that there was no new evidence to warrant further prosecutions. Seamus Mallon, the Social Democratic and Labour party MP for Newry and Armagh, pointed out that no inquests had been held, and added: “Make no mistake about it, justice has been dispensed with in this statement to cover up the murky and illegal methods of MI5 and MI6, and the darker elements within the RUC.” Mayhew responded that “inquests will, of course, be held in due course”.

That was more than 27 years ago, and the shoot-to-kill inquests have not been held. They were opened and adjourned in 1983, and reopened after Sampson submitted his reports in 1987. Eventually, the local coroner, who was charged with examining the deaths, gave up. As recently as last December, the coroner – the fifth to attempt to preside over the hearings – was complaining furiously that police had still not handed over relevant material.

* * *

During all those years, while English detectives were struggling to make sense of the dirty war, Martin McCauley had not been idle. In the summer of 2001 he turned up in Colombia. He was arrested at Bogotá airport as he attempted to leave the country on a false passport. With him were Niall Connolly, a Sinn Fein official who lived in Cuba – the republican movement’s man in Havana – and James Monaghan, an alleged leader of the IRA’s engineering department. “Monaghan is to the Provisional IRA,” the Guardian reported, “what the fictional ‘Q’ was to James Bond and the British Secret Service – an improvisational genius in the technology of killing”.

The Colombian government said it had evidence that the three men had trained the Marxist Farc guerrilla army in the construction and use of home-made mortars that fired gas cylinder bombs. They were the sort of weapon the IRA had been developing in Northern Ireland since the early 70s, and had deployed in the attack on Downing Street. McCauley was said to have been travelling to and from Colombia since 1998. The following year Farc used a number of the weapons during fighting in the town of Bojayá in the west of the country. One mortar bomb crashed through the roof of a church where hundreds of civilians were sheltering. At least 79 people were killed, around a third of them children.

The exposure of the links between the Provisionals and a militia denounced in Washington DC as a gang of “narco-terrorists”, three years after the Good Friday agreement, was deeply embarrassing for the IRA. The three Irishmen denied the allegations against them. After a trial that dragged on for eight months they were convicted of passport offences but cleared of training the Farc, and set free. They went into hiding, with the result that when the prosecution appealed and a judge overturned the acquittals and sentenced all three to 17 years in jail, he was obliged to do so in their absence. Eight months later, in August 2005, the three men resurfaced in Ireland. Today McCauley is reluctant to say anything whatsoever about his South American adventure, at one point joking that he was never in Colombia. “I was!” Cristín piped up.

* * *

The McCauleys have settled down in a terraced house on the edge of Naas, the county town of Kildare. Now 52, McCauley works as a mechanic. He rises at five each morning and spends most of his working day outdoors. He will not admit that he was a member of the IRA – to do so would be to invite prosecution – but some parts of his history are an open book. There is no extradition arrangement between Colombia and the Republic of Ireland, but the British government has made clear that he will be arrested and extradited if he crosses the border to the north.

McCauley, who is now a grandfather, looked worn-out when I met with him. Cristín said this is because he works so hard. Asked whether he supported the peace process, his response – “Yes!” – was delivered before the question is finished. Peace could not have come a moment too soon for McCauley. When he talked about the shooting at the hayshed he became visibly agitated. His speech was rapid, he grimaced slightly and he began to squirm; he could not sit still. He has never sought counselling – not because he did not believe he needed it, but because he could never trust a counsellor. “That’s the way it was, you could never trust anyone.” He talked about placing memories to one side; putting things behind him. “That’s it: you have to close doors.”

One matter that McCauley did not put behind him was his conviction for possession of the rusted Mauser rifles that were recovered from the hayshed. In late 2005, after his return from Colombia, he asked the Criminal Cases Review Commission, the UK body responsible for the examination of alleged miscarriages of justice, to look again at the case. The commission examined the evidence and referred McCauley’s firearms conviction to the Northern Ireland court of appeal.

The current DPP of Northern Ireland decided that McCauley’s appeal should not be opposed. Stalker and Sampson’s reports remain unpublished, but key sections emerged in McCauley’s case and they make sober reading, even three decades after they were written. Stalker’s report concluded that there was “ample evidence” that three senior special branch officers – whose names have been redacted in the copy of the report seen by the Guardian – had conspired to pervert the course of justice and should be prosecuted.

Sampson – who faced accusations that he had been brought in to preside over a whitewash – wrote a report that was even more forceful. He had discovered that at the very moment MI5 had been telling Stalker that it would never stand in the way of a murder investigation, and as he struggled to get hold of a copy of Tape 042, the agency was in possession of its own bootleg copy of the recording. The language of Sampson’s report betrays the anger and contempt that he clearly felt on making this discovery. “The fact that the security service was in possession of and retained the copy tape until the early summer of 1985 and did not bring it to the attention of Mr Stalker is wholly reprehensible,” he wrote. “There can be no doubt that the unauthorised copy tape held by the security service was of great significance to the Stalker enquiry. A number of senior Security Service Officers, each with a varying degree of knowledge of the tape, had more than one meeting with Mr Stalker when he was persistently endeavouring to acquire information which he considered crucial to his enquiry. These efforts to obtain the type of evidence they possessed were perfectly obvious.”

MI5 had told Sampson that the reason it did not hand over the tape to Stalker is that he did not ask them for it. “To defend their decision not to disclose this information on the grounds that he did not ask them directly for it is patently dishonest,” Sampson wrote. “Mr Stalker could not possibly have known that they possessed the very evidence he was seeking and to have frustrated his efforts in this way is nothing less than a grave abuse of their unique position.”

MI5 eventually destroyed its copy of Tape 042. Sampson recommended that the junior officer who had carried out the destruction be granted immunity from prosecution in return for giving evidence against the MI5 chief and his deputy, whom he believed should be prosecuted for “doing an act with intent and tending to pervert the course of public justice”.

* * *

The hayshed is now a store for lifesize, painted wooden figures of cowboys and Indians.

Handing down his judgment in McCauley’s appeal last September, Sir Declan Morgan, the lord chief justice of Northern Ireland, was in agreement with Sampson: “The failure of the security service to disclose the tape to Mr Stalker and to provide it to the prosecution was reprehensible.” Furthermore, the deputy head of special branch had initially misled the director of public prosecutions by leading him to believe that there was no listening device in the hayshed. “These matters amounted cumulatively to grave misconduct,” Morgan said; McCauley’s conviction was quashed.

In January, as a consequence of the Criminal Cases Review Commission investigation and the appeal court’s judgment, the director of public prosecutions announced that he was requesting an investigation into the concealment and destruction of the tape. In April, it was announced that Police Scotland would be investigating the actions of the former MI5 officers, while the police ombudsman of Northern Ireland would be investigating the actions of the former special branch detectives. It remains to be seen whether anyone will face prosecution.

Stalker, now 76 and living in peaceful retirement in the north-west of England, says he has no wish to talk about the inquiry to which his name will always remain attached. Sampson, 10 years older, is also reluctant to revisit the past.

* * *

The hayshed is still standing. I drove down the narrow lane that runs west from Derrymacash, towards the River Bann, and after a mile or so I saw it on the right, behind the redbrick bungalow. Its corrugated roof was in need of repair and the breeze-block wall to the left of the wooden double door was scarred and pockmarked. On either side of the door were grimy windows, which failed to let in more than a glimmer of light. In the window on the left there were two small holes, where the first rounds entered, striking young Michael Tighe in the heart as he sat on a stack of hay bales.

The shed was being used to store lifesize, painted wooden figures of cowboys and Indians, and soldiers from the American civil war. “I’m looking after them for a touring Wild West show,” the owner of the property explained. “Doesn’t Hiawatha look lovely?” It is tempting to think of the scene inside the hayshed as a bizarre metaphor for the Troubles: the warriors, the roughnecks and the soldiers are stored safely away, their guns holstered and their eyes seeing nothing, while outside, the world moves on.

You must be logged in to post a comment.